by Suzanne W. Jones

At the end of the twentieth century cities of the Northeast and Midwest had the highest levels of black-white residential segregation and racial isolation in the country; however, when segregation levels are measured at the block level rather than the tract level, segregation is higher in the South (Massey and Denton 223). In American Apartheid, Douglas Massey and Nancy Denton argue that “by the end of the 1970s residential segregation became the forgotten factor in American race relations” (4). They point out that “most Americans vaguely realize that urban America is still a residentially segregated society, but few appreciate the depth of black segregation or the degree to which it is maintained by ongoing institutional arrangement and contemporary individual actions” (1). In the novel Glass House (1994), New Orleans native Christine Wiltz, who is white, makes the effects of black-white residential segregation visible by presenting her New Orleans story through the diverse perspectives of residents who live in housing projects as well as Garden District mansions. Wiltz suggests that all of her readers, like all of her characters, have something to learn about the people on the other side of town.

Glass House contains a figure that Patricia Yaeger has identified as ubiquitous in earlier rural southern fiction, the dead black body, or what she terms “the throwaway body: the quick translation of white-on-black murder into economic terms, the quicker translation of black-on-black murder into nothing” (Yaeger 76). This black throwaway figure still appears in contemporary urban settings, where poor, often unemployed, black people are warehoused out of sight in housing projects or the local jail. Wiltz humanizes such throwaway bodies by giving them names, by narrating their lives, but she does not sentimentalize them. She shows that as Benjamin DeMott argued “a brutalized population will inevitably include some who come to behave like brutes” which “in turn makes it easier for the brutalizers to see themselves as policers, not causers, of brutishness” (118).

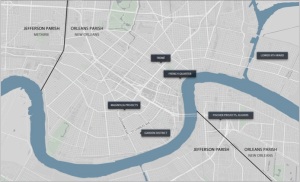

Wiltz found the catalyst for Glass House in a historical incident that strained race relations in New Orleans. In 1980 Gregory Neupert, a white policeman was killed near the Fischer Housing Project in the Algiers neighborhood of New Orleans on the west bank. Although there were no witnesses to the shooting, the police brutally questioned residents of the housing project and eventually killed four innocent people (James 14-16). In Glass House Wiltz fictionalized similar events but placed them on the east bank in the notoriously violent Magnolia Housing Project nearer the Garden District so that she could better show the effects of residential segregation, income disparity, and crime on both black and white neighborhoods. She changed Magnolia to the Convent Street Housing Project and made Louisiana Avenue Convent Street. In an author’s note Wiltz states that she chose the name as a way to emphasize that the city’s inhabitants live “cloistered” lives.

In Glass House Wiltz lays out a grid of streets that orients readers to her view of the ill effects of urban segregation as well as her vision of how integration might be nurtured. Wiltz’s fictional Convent Street crosses the real St. Charles Avenue and thus connects the Convent Street Housing Project with the mansions of the Garden District. The wide crossing street, St. Charles Avenue, serves as what the narrator terms a “buffer zone between the very rich and the very poor” (5) or as is so often the case in urban America, between whites and blacks or other minorities. Wiltz employs this intersecting street grid to illustrate the complex ways in which the lives of rich whites and poor blacks are linked, despite their spatial separation. The connection has been obscured, making for a dysfunctional relationship that the characters, both black and white, and perhaps most readers, don’t understand. While some black women from the Convent Projects neighborhood regularly cross St. Charles to support their families by working for low wages in the Garden District mansions, many black women and men are confined to the projects, which only a few white characters ever enter. Most whites who do are unnamed in the novel suggesting they are there for only one purpose – to control and corral black people in their work as police officers, almost never to solve black on black crime.

When residential segregation persists, negative media coverage and stereotyping of poor black people can solidify white notions of black people as drug dealers and welfare queens (Steinhorn and Diggs-Brown 170). Wiltz suggests that such omnipresent negative images combined with a growing number of assaults, burglaries, and vandalism in the Garden District produce a climate of white fear that through a twist of faulty logic becomes a fear of all black men, to say nothing of a grave misunderstanding of the culture of poverty, which has evolved into a lack of sympathy for poor black people. Wiltz represents the fear of the other entering one’s enclave (white police storming the Convent; black men plundering the glass houses of the Garden District) as a psychological contagion, with the result that inhabitants on both sides of the color line are arming themselves.

When one of the white characters, Thea Tamborella, returns to New Orleans, just briefly she thinks, in order to settle her Aunt Althea’s estate after ten years of living in Massachusetts, the taxi driver on the way from the airport recommends that she purchase a gun. At a homecoming dinner party, a high school acquaintance, Lyle Hindermann, places his handgun prominently on the dinner table next to a bowl of yellow flowers and a silver candlestick (53), punctuating his point that Thea needs a gun because as he says, “They’re all armed, so we have to be armed too” (53). Several characters – young and old, black and white – are shot and killed in this novel, but they are all innocent victims. Wiltz suggests that guns bought for self-defense too easily end up in the wrong hands. Thea reminds Lyle that when she was a child, her parents were shot with the very gun they bought for protection. Later in the novel, the gun that Lyle foists on Thea’s friend Bobby is stolen when his house is burgled.

From the distance of their Garden District neighborhood, white characters like the Hindermanns, see themselves as victims and black people in the Convent Project as the enemy. While Wiltz does not shy away from depicting black on white crime, she represents the rich white people, as victims of their own social myopia, not simply as victims of the black people they fear, and in many cases, have grown to hate. Lyle, a banker during the week, is so consumed by his desire to protect his white neighborhood that he ruins his own relationship with his wife and children by spending all of his free time as a reserve policeman.

Before we enter the Hindermanns’ home, one of the glass houses of her title, Wiltz makes sure that her readers first see New Orleans race relations through the eyes of those who live in the projects. She presents the Convent Street Housing Project as both “a dangerous place to live,” filled with “jobless people whose hope of finding work dwindled as the jobs themselves did” (18) when the oil boom went bust, and as a place filled with people trying to live a decent life. According to Massey and Denton in American Apartheid the crux of the problem is that the popular media and some scholars have severed what has been termed “the culture of poverty” from its roots in unemployment, social immobility, and residential segregation (5). In Glass House Wiltz re-grafts those roots. When the price of oil collapsed in the mid 1980s, New Orleans went through very difficult economic times, which older New Orleanians compared to the Great Depression (Lewis 121). Through the eyes of black characters who live in the projects like Janine and Burgess, Sheree and Dexter, readers see both the cycle of unemployment, illiteracy, and unwed childbearing that entraps them, and their often heroic attempts to break free: learn to read, find a job, establish a nuclear family. Wiltz enables readers to experience the motivating factors for the behavior of her poor black characters. But the structural ironies Wiltz uses in plotting Glass House create an overwhelming impression of how difficult it is to break the cycles in which the characters, both black and white, are caught.

Wiltz, who began her career writing detective fiction, intricately constructs her plot in interlocking ways to point up the hidden connections between rich whites and poor blacks that residential segregation obscures. For example, when a rash of burglaries occurs in a white-flight neighborhood in neighboring Jefferson Parish, the local white sheriff calls a press conference to announce that “any suspicious-looking black males seen in all-white neighborhoods would be stopped and questioned, especially those driving shabby, disreputable cars” (116). Angered by such blatant racial profiling, Dexter who lives in the Convent Project organizes a parade of black men in old cars, radios blaring and streamers trailing from their antennas. They cruise through Jefferson Parish, with Dexter as their grad marshal, resplendent in buttery soft, blue leather and ensconced in a customized white Cadillac. What white people like Lyle see as unmotivated lawlessness, Wiltz portrays as total frustration with institutionalized racism. Ironically though, the attention Dexter calls to himself, while garnering kudos from the black community, leads weekend deputy Lyle Hindermann to think that Dexter is the drug kingpin in the projects and to ambush his apartment. Having observed several black men enter Dexter’s apartment for only a few minutes at a time, Lyle assumes they are there to buy drugs; he never imagines they are simply congratulating Dexter on organizing the protest parade.

The structural ironies Wiltz uses in plotting Glass House create an overwhelming impression of how difficult it is to break the cycles in which the characters are caught, which hold them in place. For example, Dexter’s girlfriend Sheree’s precaution of having him move in with her for safety actually leads Lyle to kill her when he tracks Dexter to her apartment. In a similar series of ironically related incidents, the cleanup effort that the real drug kingpin Burgess masterminds in the Convent Project results in his death. His minimal but noticeable changes – fresh paint, repairs, a communal garden, and a child-care center – attract the attention of the police, who know that the city has not provided the money for such improvements. Burgess’s well-meaning but unorthodox urban renewal leads to their assumption that drug money is involved, even though Burgess is not selling drugs in the Convent. Police suspicion that he is results in Dexter’s harassment and Burgess’s need to go underground. This outcome, of course, brings a halt to Burgess’s improvements and his presence, making way for a rival gang to terrorize people in the projects and ultimately to kill him.

Because Thea knows Burgess and Dexter and Lyle, she can see the connections in what appear to be unconnected events, leading her to an important realization about the city’s “collective fate”: “For she was quite certain that such a thing did exist, [it was] bigger than any one person’s fate, or even one race’s fate, bigger than them all.” (141). Similarly readers, by following the cause and effect structure of Wiltz’s plot and by seeing the very real links between racial enclaves, are encouraged to discern the underlying causes for urban violence and racial tensions, just as they might look for clues in one of her murder mysteries. Wiltz creates two characters who bridge the distance between these two segregated neighborhoods: Thea, the white woman who grew up in her aunt’s Garden District home after her parents, her Italian immigrants, were murdered, and Burgess, the black drug dealer/renovation expert who grew up in the Convent Street Housing Project. Much to the shock of her white neighbors, Thea hires Burgess and his black crew to renovate the house she has inherited. Wiltz makes their unlikely friendship plausible because they knew each other as children when Burgess’s mother Delzora worked as Thea’s aunt’s housekeeper.

While Wiltz uses Thea to reveal the complex anatomy of white fear, she uses Burgess to reveal the equally complex anatomy of black rage. Readers of Glass House see fear close enough to understand how fear provokes fear and misunderstanding generates more misunderstanding. Most importantly readers see how white people’s misconceptions, if not outright prejudices, are a large part of the problem because they influence, not just personal interactions, but ingrained institutional and social practices. Wiltz shows that the police are prejudiced and the housing authority oblivious to the problems in the projects, problems that Burgess attempts to rectify. But she also shows how social practices exacerbate the problem. Sandy Hindermann tries to convince Thea to fire Burgess and his crew because their work is unknown in their social set, but Thea remains loyal to Burgess, reminding Sandy that “if Burgess and his carpenter never get any work, how will they ever have anything to show?” (99).

Because her decade away in Massachusetts enables Thea to view New Orleans residential segregation from another perspective and because she sees Burgess as more than simply a drug dealer given their history, their business relationship, and their growing friendship, she decides not to terminate her relationship with him after she learns that Burgess has been a drug dealer. Thea’s unexpected welcome when she next sees him, disrupts the pattern of white response Burgess expects and makes him feel comfortable enough to try to explain how he can be both a law breaker and a benevolent community leader. During this conversation, Burgess makes several presumptuous remarks about white people, which anger Thea. He stereotypes her (“someone like you”), and he assumes that she cannot understand “black reality” because she lives in a totally different world – “you white; you safe” (160). Her response is to remind him that although he may feel safe in her house that she does not feel safe there because her boyfriend Bobby was mugged outside and because her parents were murdered in an incident in which drug use may have prompted the violence. Wiltz employs this conversation to shed light on what each does not understand about the other’s reality—whites in the Garden District do not understand why poor blacks might be led to crime and poor blacks do not understand why whites might stereotype them as criminals.

Although Thea’s anger kindles his, Burgess knows that unchecked anger will block his ability to care about making her understand him and will frighten Thea, pushing them further apart. Through their frank exchange, in which they talk through their anger and apologize for misunderstandings, Wiltz models the possibility of productive interracial dialogue. While this scene works to show that understanding is possible, its orchestration is definitely a white perspective on the process: more white anger should be allowed, black anger should be moderated more often, and “old anger” should not be infused into current situations. Given the many venues Wiltz explores in this novel, it is not surprising that she chooses Thea’s house for frank dialogue about unspoken racial tensions. For it holds memories of the burden of southern history that must be understood, and it is the only place where blacks and whites have come together at work, at meals, and at play. Furthermore, both Thea and Burgess want the other to understand and both are open to a different point of view. Sociologists have determined that simple integration is not enough to deconstruct stereotypes and that contact between the races may lead to more prejudice if the contact occurs between unequals who have different goals and very different cultures. Psychologist Y. Amir would no doubt suggest that the chemistry Wiltz creates is exactly right between Burgess and Thea because of their shared history, their growing friendship, their mutual goal of renovating her house, and their willingness to see each other as so much more than the way others might categorize them, as a black drug dealer and a rich white lady.

Readers dwell in the possibility of racial integration in Thea’s home and in her way of doing business. But they leave the novel much as they began it with Delzora still traveling Convent Street, working in the same home, albeit for a more benevolent and unprejudiced white employer, but with her only son dead and his child to grow up like hers did without a father. That Wiltz concludes Glass House with Delzora’s paradoxical musings –“Nothing had changed but everything had changed” (189) – underlines the fact that residential segregation, institutional racism, and the long legacy of prejudice will not be changed by the goodwill of a few good people.

Illustrations

1. Actual locations in New Orleans. Map created by Nathaniel Ayers, University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab, May 2012.

2. Locations as fictionalized by Christine Wiltz in Glass House. Map created by Nathaniel Ayers, University of Richmond Digital Scholarship Lab, May 2012.

3. Census maps are from the Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. http://www.nhgis.org.

Works Cited

Amir, Y. “The Role of Intergroup Contact in Change of Prejudice and Ethnic Relations” in Toward the Elimination of Racism, ed. P. A. Katz. New York: Pergamon Press, 1976.

DeMott, Benjamin. The Trouble With Friendship: Why Americans Can’t Think Straight About Race. 1995; New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

James, Theresa. “A Conversation with Chris Wiltz.” Xavier Review 15.2 (Fall 1995).

Jones, Suzanne W. Race Mixing: Southern Fiction since the Sixties. pp. 269-279. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004. Revised and reprinted with permission of The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lewis. Peirce F. New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape. Santa Fe, New Mexico: Center for American Places, 2003.

Massey, Douglas S. and Nancy Denton. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Steinhorn, Leonard, and Barbara Diggs-Brown. By the Color of Our Skin: The Illusion of Integration and the Reality of Race. [1999] New York: Plume, 2000.

Wiltz, Christine. Glass House. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994.

Yaeger, Patricia. Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930-1990. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.